Contributing Authors: Lindsey Beatrice, Elias Berbari, Cole Dickerson, Sarah Thorson | CU Boulder MENV

This disclaimer informs readers that the views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in this blog belong solely to the author, students of CU Boulder’s Masters of the Environment (MENV) program and their research, not necessarily to Nourish Colorado as an organization, nor does the blog represent the work that Nourish Colorado is leading.

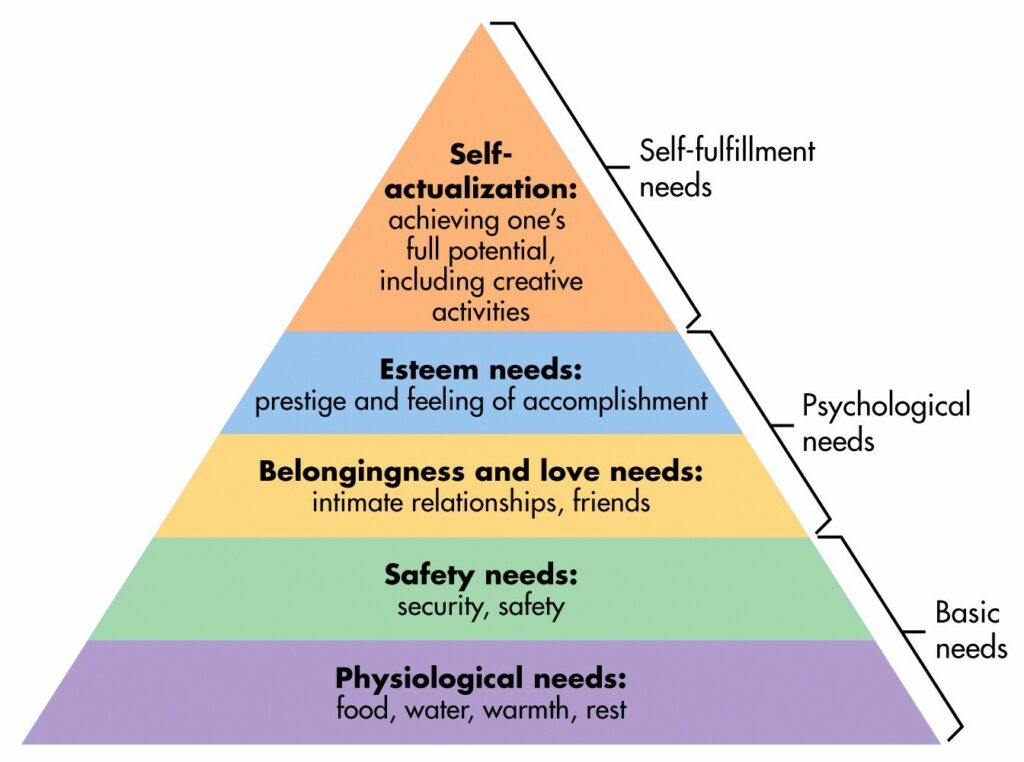

On Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, food is a basic need that must be met for every single person before they can truly focus on meeting psychological needs and self-fulfillment. Think about it: when you’re hungry it’s harder to focus, you can get hangry and impatient, and your body and mind aren’t properly fueled to support you in accomplishing your tasks for the day. Having access to food is a necessity, but consuming only empty calories can lead to co-existence of obesity and malnutrition. Nutrition security goes hand in hand with food security—if the only foods available to us do not contain the nutrients, vitamins, minerals, and components that properly nourish our bodies and minds, that’s known as nutrition insecurity.

We believe access to healthy, nourishing food is a human right. Millions of Americans experience food insecurity, and the financial instability many people endured with COVID-19 made the problem worse. The good news is that there are a lot of things we can do to meet this basic human need at different levels of government! Improving policy and public services can tackle some of the root causes of food and nutrition insecurity and help us create an equitable food system where no one goes hungry.

An equitable food system that enables all people to be food secure must meet the following metrics:

- Access: Are there options available for healthy food nearby?

- Affordability: Are those options at a price point that people in the area can afford?

- Proximity: How close are food retailers/markets, and are there easy ways to get there via public transit or walking/biking?

- Quality: Are foods easily available to residents nutritious and filling, rather than just empty calories?

- Relevant: Does the community have access to the kinds of foods they want and need?

- Restorative: Do the foods available regenerate the earth and are the workers along the supply chain treated with dignity and respect?

So how can we build a better food system that checks off all of those boxes? It may seem hard, but actually, cities and states can make major improvements with policy choices that are fully within their control. When talking about complex problems like food and nutrition insecurity, there are downstream and upstream solutions. Downstream solutions treat symptoms of the problem, and are absolutely necessary to alleviate suffering and help people meet needs in the moment. But we can’t only focus on downstream solutions because it doesn’t change the root cause of the issue, and that’s where upstream solutions come in. These focus on making changes that minimize or solve the problem in the first place.

Boosting food security through wages and social programs

When it comes to making healthy food more affordable, cities can use upstream and downstream solutions. Since 2001 wages have effectively decreased at a rate of 0.1% per year while rent prices have risen 3% in the same timespan, and the cost of food has increased by about 2.3% in the past decade. Increasing the minimum wage for a city or a whole state addresses a primary upstream cause of food insecurity—millions of working people do not make enough money to meet their basic needs. Economic security makes food security possible.

If we increased the federal minimum wage to $15/hr by 2023, food security would be attainable for an additional 1,200,000 households, providing a major boost to working single-parent households who currently don’t earn enough to buy sufficient amounts of enough food every week to meet their needs. When faced with hard financial choices, rent and bills come first and food budgets are often sacrificed. Helping folks improve their credit scores decreases monthly interest rates, and putting policies in place to reduce rent increases and make housing more affordable would help many families have a bigger budget for nutritious food. Along the same vein, student loan and medical debt relief would remove huge financial burdens for low- and middle-income households that struggle with food security.

However, those upstream solutions can take a while to be passed, implemented, and for communities to start feeling the effects. We also need programs that address downstream needs and can stretch dollars further. Colorado and 28 other states have an initiative called Double Up Food Bucks that allows people participating in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) to match their SNAP benefit dollars with more dollars to be spent on produce from farmers’ markets, retailers with local foods, and even community supported agriculture (CSA) programs. If someone buys $10 of produce at a farmers’ market with their SNAP card, they will get a $10 match back onto their SNAP card. In 2020, this enabled $11,740,000 worth of healthy food purchases for families across the US.

Statewide policy can also have a major impact on nutritious food access. Starting in 2018, the Colorado state legislature began funding the Food Pantry Assistance Grant. This program had two main goals in its inception: to increase the amount of fresh and nutritious foods in food pantries around the state, while providing business opportunities to Colorado’s farmers and ranchers through a local procurement mandate. Essentially, the program provides funding to food pantries to buy food from local producers. The funding amounts were greatly increased in a 2020 special legislative session to support our communities during the challenges brought about by COVID-19. Reports covering grant cycles from 2019 and 2020 show promising impacts for various stakeholders. Currently, a group of MENV students are working on a comprehensive analysis and evaluation of all cycles of the grant program as their Capstone project; they are hoping to provide recommendations for the program to strengthen regional food systems and overall food security in post-pandemic Colorado.

Investing in infrastructure for food security

Making nourishing food more financially accessible to people has a significant impact, but it’s not enough. Investing in infrastructure which promotes food security is also necessary, but often overlooked from a policy point of view. One of the more salient challenges present for people to access food is a lack of transportation. Though you may have a car to drive to the farmers market, or be able to bike to your local CSA pickup, many people aren’t transportation secure. In 2019, close to 34 million people used public transportation EACH weekday in the United States. There has been a 28% growth in public transportation ridership since 1995 compared to a 23% growth rate in population, indicating that a significant number of people are transitioning to rely on public transportation.

Leah Penniman, a prominent farmer, author, and spokeswoman for BIPOC representation in agriculture, details the barriers her family faced to accessing healthy food in her book, Farming While Black. She was living with her partner, trying to raise two kids and looking for work. There were no farmers markets or co-ops in proximity to their house, and with no personal transportation, there was little they could do to travel to an area which had healthy food. Even with two college degrees between them, Leah and her partner struggled to access local and healthy food. Finally, they found a CSA that had a pickup location 2 miles from where they lived. Leah walked to the pickup location every week with her two children, two miles each way, to get nourishing food. Obtaining the right food for us and our families shouldn’t be this hard, yet too often it is.

Researchers in public health fields have found that communities that are transportation insecure are more likely to be food insecure and have higher rates of developing cancers and other diseases. And this correlation didn’t occur by happenstance, or due to a lack of motivation on the part of the community’s residents; decades of structural racism and economic disinvestment played a powerful role. As President Biden pushes for a hefty infrastructure plan, transit equity should be prioritized given its ability to improve access to food and financial security through enhanced job opportunities, and it’s impact on reversing redlining and segregation in cities.

Recognizing food as a human right

Cities and states can also promote policies that seek to create more accessible, resilient, and sustainable food systems. They can allocate tax dollars, set priorities for where funding goes, and can reflect community desires for more secure livelihoods. Right-to-food legislation has existed in some form for decades, and in 1976 the UN recognized the “right of everyone to an adequate standard of living…including adequate food,” however, the US never ratified the treaty. Now, some states are recognizing food as a basic need and thus a human right. Maine’s House of Representatives just approved an amendment to their Constitution that food is “a natural, inherent, unalienable right.” A co-sponsor of the bill said its purpose is to ensure that the government cannot interfere with an individual’s right to decide how to feed themselves. While the focus is less on food security than individual rights, it is a step in the right direction and could be open to interpretation by courts. West Virginia went a step further, introducing an amendment that recognizes West Virginians’ “fundamental right to be free from hunger, malnutrition, starvation and the endangerment of life from the scarcity of or lack of access to nourishing food,” to be voted on in the January congressional session.

Some cities are even passing Food Action Plans, similar to the Climate Action Plans that have been enacted in cities and states around the country. The overarching goal of a Food Action Plan is to support both people in their right to food access, and ensure resilience and security for food producers to enhance local food systems. Santa Barbara has the additional goal of “future-proofing” their food system, Seattle aims to increase access and grow opportunity while decreasing waste, and Denver wants to “create a more inclusive, healthy, vibrant, and resilient” city. The state of Colorado also has a Blueprint to End Hunger. These plans help set legislative and funding priorities that drive community investment and better collective outcomes. You can advocate for your city to develop a Food Action Plan that prioritizes food and nutrition security for all by contacting your mayor’s office, bringing it up at a town hall event, or getting involved with organizations involved in food access and policy.

Food security that meets community needs

Often overlooked, community needs are another important aspect of food security. After all, what good is access to fresh and nutritious food if you lack the time or resources to prepare it? We need to understand the other constraints and complexities of communities who experience food insecurity so we can address it in ways that truly are impactful. Many people (or even schools and organizations) may not have adequate kitchen amenities, or people who are food insecure may be differently abled. Everyone deserves to have their needs met. So what can be done? First, more research and attention should be paid to understand how food insecurity impacts EVERYONE in food insecure communities. Research in these areas often exempts those who have disabilities and often struggle with food insecurity. Then, there must be more funding given to leaders and organizations who understand their communities and connect resources to all who need them.

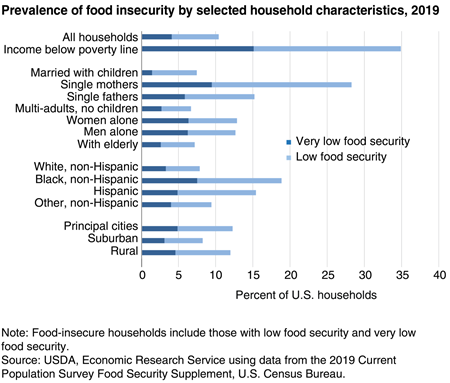

We also need to consider the co-existing challenges that are often coupled with food access. Food insecurity rates are highest for single mother households, but being a single parent is exhausting and they might not have the energy, time, or resources to buy and prepare healthy meals from scratch every single day. Households with food insecurity might also struggle with keeping the electric bill paid, and might not have reliable refrigeration for a week’s worth of produce. Creating spaces to access fresh, local, affordable food during any day of the week is important, as is providing prepared meals using healthy ingredients.

This means we need to get creative in some of our solutions. For example, startup ReKaivery in Fort Collins is a small farmers’ market and fresh food vendor that will accept SNAP/EBT. They’ll operate Sunday – Friday, rather than having a traditional Saturday market, which allows folks to come and buy what they need when they need it and gives access flexibility to those who might have a varied work schedule. Denver-based MetroCaring operates a market where people can procure food free of cost and hosts cooking classes in multiple languages. But they go further to help people obtain legal documents they need for employment, housing, healthcare, and social services—this gets at some of those upstream causes of food insecurity.

Using public institutions like schools is another angle to boost food and nutrition security, as many children and youth get a majority of their calories at school during school days. But most of the culinary teams in schools have been limited to using pre-packaged foods and may not have the skills necessary to prepare healthy meals for students from fresh, local foods. Nourish Colorado has a program, LoProCO, to provide resources to institutions for increased local food procurement and preparation of nourishing foods. Nourish provides culinary training to kitchen staff as well as facilitating connections with local food producers to ensure institutions have everything they need to succeed in providing fresher, healthier foods.

How can I get involved?

All in all, food and nutrition security is incredibly complex, and must be approached from multiple angles. We need upstream and downstream interventions, creative solutions that address co-existing needs and remove barriers, and a recognition that everyone has a right to healthy, nourishing food.

And there are so many ways to get involved in making change! Food policy councils often focus on reducing food insecurity and providing residents with nourishing local food. Membership ability can differ from council to council, but you can always contact them with your thoughts and concerns or reach out to get information about volunteering or supporting. Check out Denver’s or do some internet sleuthing to find out if your city has one (you can also reach out to Wendy Peters Moschetti, Director of Strategic Initiatives at Nourish, if you want to get connected to a nearby coalition).

You can also join one of the Colorado Blueprint to End Hunger’s 5 work groups by signing up here. Each one has a different focus area, so you can help with something that matches your skills. Additionally, the Biden Administration’s American Rescue Plan (ARP) gives funds to municipal and county governments. Write, call, and email your local elected officials to tell them to prioritize using those funds for food and nutrition security. Once funds are allocated, reach out to the organizations involved to find out how you can help!

Smart policy, political will, and persistence will help us ensure that no one goes hungry or undernourished in the U.S. Dive deeper and get involved!