By Liz Holland & Sarah Thorson, with research assistance by Elias Berbari | CU Boulder MENV

This disclaimer informs readers that the views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in this blog belong solely to the authors, students of CU Boulder’s Masters of the Environment (MENV) program and their research, not necessarily to Nourish Colorado as an organization, nor does the blog represent the work that Nourish Colorado is leading.

What do we mean when we talk about ‘food justice’? This term can be defined as “a holistic and structural view of the food system that sees healthy food as a human right and addresses structural barriers to that right.” A fully just food system would provide the ability for all people to exercise their right to grow, sell, and eat healthy food.

In referring to all people, we must include those on the front line of the food system: farm workers. For the purposes of this article, farm worker and frontline worker will be used interchangeably to describe the 2.4 million people who work on farms and ranches across the United States. According to a review of 10 national studies, food insecurity among farm workers ranges an average of 50-65%, and is as high as 82% in the Southwestern US. While it may seem counterintuitive that so many of the people who grow our food don’t have enough to eat themselves, there are structural factors within our society contributing to these high rates of food insecurity among farm workers, such as low wages, lack of transportation, bureaucratic challenges in attaining food assistance, and other barriers that limit access. To ensure food security for farm workers (as well as the rest of us), several of these critical barriers must be addressed.

Land ownership is concentrated with white males, and farm labor in the hands of black and brown people – How did we get here?

Structural barriers to food justice can be viewed differently, but a key issue at the foundation lies in individual relationships to the land itself. The Native people of Turtle Island are the original stewards and ‘farmers’ of the land we know as the United States. As colonizer ships arrived, a long history of land dispossession and slavery (used heavily in agriculture) ensued in this country. The US expanded across the continent and indigeneous folks were removed from their home lands and relocated to reservations, then slaves were brought from Africa to work the land instead.

As time went on, Black, Indigeneous, and People of Color (BIPOC) were disenfranchised from the land they once farmed through the passage of laws such as the 1862 Morrill Act, geared towards funding land grant universities focused on educating new white land owners. Later the second Morrill Act of 1890 was used to establish land grant universities for newly freed slaves, though these new ‘sister’ schools did not receive the same funding as their white counterparts, further disenfranchising those who were freed but not given provisions to live. The 1914 Smith-Lever Act, which created the Cooperative Extension Service, further educated white landowners on researched agricultural practices and established capacity funds that were not made available to the new institutions founded in 1890.

BIPOC people were further removed from the land in a multitude of ways. Newly freed slaves were once promised 40 acres of land and a loaned mule, only to have this order reversed. Indigenous children were taken from their homes and made to assimilate to a foreign culture, one that removed them from their ancestral lands. Anglo cattle ranchers stole land from Native ranchers through violence, theft and utilization of title disputes.

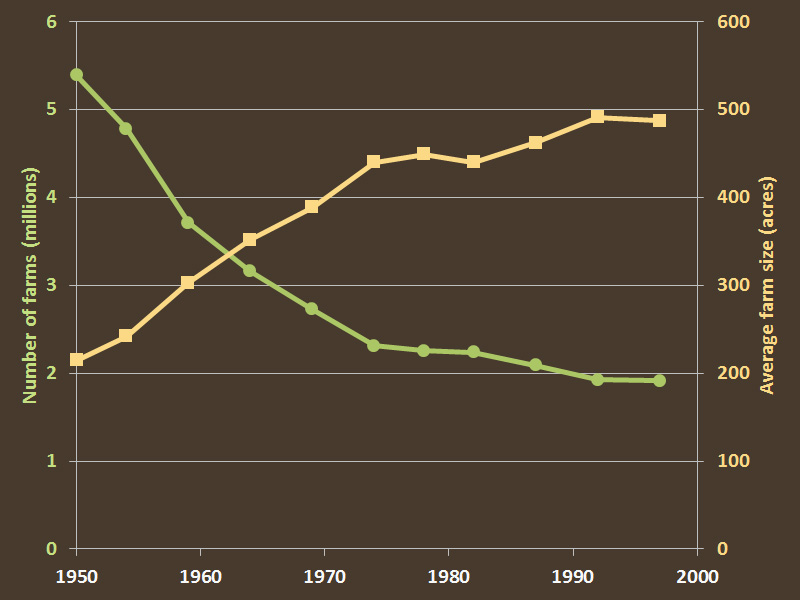

In addition to the tactics above, the passage of time (and more laws) also caused the size of the average farm to grow. Large-scale agribusiness and commodity crops have been incentivized by the government, supporting the rise of monoculture food systems and prioritizing corporations over small-rural farms across the US. The US Department of Agriculture (USDA) defines a “small” farm as an operation that grosses under $250,000 cash income per year, a definition which has further distinctions between small commercial (selling more than $10,000 worth of goods) and noncommercial (selling less than $10,000) operations.

The Congressional Agricultural Acts passed in the 1970s prioritized large corporations by decreasing payments to farmers and ending marketing quotas and acreage allotments. The resulting consolidation of farmland has led more small farmers to lose their land and way of life, and recent numbers are staggering. According to Time, “the nation lost more than 100,000 farms between 2011 and 2018; 12,000 of those between 2017 and 2018 alone.”

Human rights for agricultural workers

We have created a system of land ownership and power in agriculture with a concentration of farm labor that is clearly defined along racial (and gender) lines. Where does our current food system leave its frontline workers?

Another structural barrier to food justice can be seen in the relationship farm workers have to their communities and society at large. For over 30 years, the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA), responsible for establishment of minimum wage and overtime pay for laborers, excluded farm workers. The law changed after 1966 to include farm workers, but still didn’t assure them overtime pay, and instead of hourly wages, they are paid by the amount of produce picked or units processed, keeping wages lower. The 2015-2016 findings from the National Agricultural Workers Survey report the annual income of an individual farm worker is below the poverty level, falling between $17,500 and $19,999. To complicate matters further, 75% of farm workers are foreign-born individuals, 49% of whom lack immigration status in the US. Yet when it comes to farm workers’ rights, low wages and immigration concerns are just the tip of the iceberg. According to a 2012 report from the Food Chain Workers Alliance, 40% of surveyed folks worked more than 40 hours a week; 79% of workers did not have sick days or didn’t know if they did; 83% did not receive health insurance from an employer; and 58% were without health insurance at all. In 2016, another Food Chain Workers Alliance report shed light on the wage disparities that exist among groups working along the food chain:

For every dollar earned by white men working in the food chain, Latino men earn 76 cents, Black men 60 cents, Asian men 81 cents, and Native men 44 cents. White women earn less than half of their white male counterparts, at 47 cents to every dollar. Women of color face both a racial and a gender penalty: Black women earn 42 cents, Latina women 45 cents, Asian women 58 cents, and Native women 36 cents for every dollar earned by white men.

No Piece of the Pie, Food Chain Workers Alliance

What’s been happening lately?

This long history of land dispossession and unfair wages, along with additional structural barriers, has led to the high rates of food insecurity among frontline workers mentioned above. To fill this gap and put food on their families’ tables, farm workers utilize federal nutrition programs such as Supplemental Nutrition Assistance (SNAP), Women, Infants and Children (WIC), and the National School Breakfast and Lunch program. Regional assistance organizations like food pantries and soup kitchens, while offered as a service, often are not utilized by farm workers as they are either 1) ineligible due to documentation status; or 2) eligible but want nothing to do with the federal government, don’t want to provide papers, etc.

At the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, farm workers were deemed essential as government officials feared what would happen to the larger food supply chain if they were to stop working, placing these frontline workers at higher levels of risk than the general population. As farmers around the country plowed perfectly good produce into their fields and dumped milk into ditches, farm workers were still struggling to feed themselves and their families. In response, groups mobilized to support local frontline workers. For example, Project Protect in Colorado delivered over 14,500 boxes of food to over 5,600 farm workers and over 3,000 non farm workers. While these efforts won’t fix the root problems of this systemic issue, they successfully secured food at the table for those securing food at ours.

Getting to the Colorado Agriculture Worker Rights Bill

In the 1950s and 60s, two activists by the names of Dolores Huerta and César Chávez started the United Farm Workers (UFW) (formally National Farm Workers Association and Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee). The efforts led by this group, primarily impacting California, helped pass the first farm labor law in the country that required employers to pay farm workers fairly, allowed farm workers to collectively bargain/organize, and required employers to provide safe working conditions, among other important protections. Since this time, several other states have passed similar legislation to protect farm workers. However, in the light of COVID-19, farm workers were deemed essential while many still did not have the basic protections needed to be safe during this time.

This led Project Protect Food Systems to pen Senate Bill 21-087 in the state of Colorado, which would ensure basic protections for farm workers, including meal and rest breaks, overtime pay, the right to collective action, minimum wage requirements, and access to services. Through tireless efforts by many and the support of additional groups and individuals, both within the agriculture and adjacent sectors, the bill was signed into law in June 2021!

How to further support our farm workers

While this is a huge step towards justice for farm workers in Colorado and addressing the high levels of food insecurity they face, there is still more we can all do to support those who put food on our tables.

Adopted from a report by the Food Chain Workers Alliance, here are a few ways that consumers can support farm workers:

- Support producers who provide livable wages, benefits and opportunities to their workers. When you buy from our Colorado producers, such as through a CSA, at a grocery store or at a farmers market, ask them about who works on their farm. Let them know you want to support farmers and all farm workers!

- Tell policymakers you will not support exploitative policies that lack protections such as minimum wage, health benefits, wage theft and other issues associated with the food system.

- Include farm workers and farmers in every conversation you have about the sustainable food system. In doing so, you can help other consumers make more informed decisions about the food they are purchasing.

Additional actions to support farm workers’ rights:

- Show your support for policies and legislation that ensure farm workers’ rights. For example, a federal Fairness for Farm Workers Act was recently introduced in the House of Representatives in May, 2021. Contact your Representative and share your thoughts on the Bill, sign up to receive updates, and find additional ways to take action.

- Sign petitions and forms associated with broadening the protections for farm workers in your state. Use sites like Change.org to find petitions that have been started in your community.

- Consider donating to groups working to secure farm worker rights. The systemic degradation of our food system needs not only human power but financial support as well. In Colorado, examples include Project Protect Food Systems and Cultivando, and on a larger scale, the Food Chain Workers Alliance represents workers in the US and Canada.

- When legislation is presented that improves the livelihoods of farm workers, ask organizations that you are a part of to support the policies publicly.

- And lastly, talk to your farmers and farm workers. Having conversations with them can give you first hand knowledge on what needs are and are not being met in our current system.

Additionally, here are ways you can help support small farms:

- Sign up for a CSA, or Community Supported Agriculture box. These usually pre-made boxes of produce allow the consumer to have fresh fruits and vegetables each week and provide the farmer with secure income early in their season. LocalHarvest and the USDA both have tools to find a CSA near you!

- Shop at the local farmers market. Similar to a CSA, the consumer benefits by being able to pick up fresh, nutritious food while providing the farmers with a source of income each week. Buying directly from farmers also allows them to retain a higher percentage of each dollar you spend on food (as opposed to the average 14.3 cents farmers receive for each retail food dollar).

- Eat seasonal foods when you can and preserve them for off seasons. Guides from Seasonal Food Guide and the National Center for Home Food Preservation help consumers understand which foods are growing at different times of year and teach how to store those same foods for off season times.

If you are interested in joining a live and in-person discussion around these and similar issues, keep an eye out for upcoming information about an event in October! Exact date, additional details, and registration TBA.